What is Systematic Theology?

Systematic theology is the study of the Bible’s doctrine designed to help us shape a proper worldview. Systematic theology presupposes that the Bible gets reality right, and it assumes Scripture’s overarching unity while affirming the progress of revelation and the development of redemptive history. In Systematic Theology, we seek to answer the question, “What does the whole Bible say about X?”

In the interpretive process, the stage considering Systematic Theology is asking more specifically, “How does our passage theologically cohere with the whole Bible?” Or, “How does our passage contribute to our understanding of certain doctrines?”

Traditionally, systematic theology divides into at least ten categories:

- Theology Proper (the doctrine of God)

- Bibliology (the doctrine of Scripture)

- Angelology (the doctrine of angels and demons)

- Anthropology (the doctrine of humanity)

- Hamartiology (the doctrine of sin)

- Christology (the doctrine of Christ)

- Soteriology (the doctrine of salvation)

- Pneumatology (the doctrine of the Holy Spirit)

- Ecclesiology (the doctrine of the Church)

- Eschatology (the doctrine of the end times or last things)

Different theological views within the church arise from different perspectives on each of these topics.

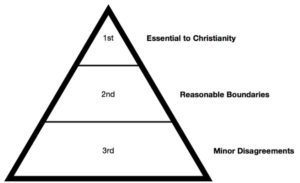

It’s important to recognize that not all doctrinal issues bear equal weight. For example, Paul emphasized that the gospel he preached was of “first importance” (1 Cor 15:3). Other teachings matter, but nothing is more fundamental than the good news that the reigning God saves and satisfies sinners who believe through Christ Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. To say that certain doctrines are more important than others does not imply that Christians may take any biblical truth less seriously. All doctrines matter, but certain ones are more fundamental––more foundational––than others because they undergird and inform all biblical truth. Furthermore, recognize that your conviction on a doctrine may influence your understanding of another doctrine.

Albert Mohler has termed the weighing out of different doctrines theological triage.[1] In Systematic Theology, theological triage involves assessing those doctrines that require the church’s greatest attention. Assessing means you as the busy expositor must classify your passage’s doctrines as primary, secondary, or tertiary.

The Process of Theological Triage

1. Level 1: Doctrines Essential to Christianity

First level issues of doctrine are those most central and essential to Christianity. You can’t deny these issues and still be a Christian. Mohler includes here doctrines such as the Trinity, the full deity and humanity of Jesus Christ, justification by faith, and the authority of Scripture.

2. Level 2: Doctrines that Generate Reasonable Boundaries

Second level issues are usually those that distinguish denominations and local churches. These are issues that commonly spark the highest-level debates, are usually grounded in some form of biblical interpretation, and generate reasonable boundaries between Christians. Mohler includes among these the doctrines of the meaning and mode of baptism and views on the role of women in the home and church. To these, I add the questions of God’s sovereignty in salvation and of divorce and remarriage. Level two differences do not identify someone as a Christian, but most local churches will struggle if their leaders disagree on these matters.

3. Level 3: Doctrines Addressing Minor Disagreements

Third level issues are those doctrines over which Christians can disagree and easily remain in close fellowship, even within local congregations. These are matters of wisdom, conscience, and practice like, “Should Christians participate in Halloween?” or “Is it best to educate children through public school, private school, private Christian school, or homeschool?” Other times third-level issues are matters of simple dispute bearing little influence on one’s everyday life. Mohler includes among these questions about the millennium and those related to the timing and sequence of Christ’s return.[2]

How to Study Systematic Theology

Approaching the Bible’s doctrines is no light matter, for we are seeking to grasp all that God has revealed in Scripture on a given topic. I propose the following approach to the study of systematic theology.

1. Ask God to Supply Both Insight with Reason and Humility with Love

There are at least two reasons why all pursuit of doctrine must begin with prayer. First, we do not want to be ashamed of failing in rigorous, God-dependent thinking (1 Cor 14:20; 2 Tim 2:7). Failing at this point is serious. As Peter notes, “There are some things in [Paul’s letters] that are hard to understand, which the ignorant and unstable twist to their own destruction, as they do the other Scriptures” (2 Pet 3:16). Second, we need the Spirit’s aid to gain the experiential knowledge the Bible demands. This kind of experiential knowledge of God is only “spiritually discerned” (1 Cor 2:14; cf. Eph 1:17–19), and because of this, we must saturate with prayer our quest to grasp Bible doctrine.

2. Catalog and Synthesize All the Relevant Passages

After praying, collect the most relevant passages related to the topic with which you are wrestling. The best tool here is a concordance (see Word- and Concept-Studies post), which will allow you to look up keywords or concepts to find where the Bible treats your subject. Once you have identified the most relevant texts, you need to classify them. This process entails reading all the texts carefully, summarizing their points, and organizing them into groups based on distinct patterns or features. Ever keep in mind the flow of salvation history and the progress of revelation! The final step is to synthesize in one or more points what the Bible teaches on your topic and then to clarify how your passage contributes to this understanding. If your passage were not present in Scripture, would some crucial knowledge about your topic be missing?

A Case Study in Systematic Theology

Yahweh declares in Zeph 3:9–10: “For at that time I will change the speech of the peoples to a pure speech, that all of them may call upon the name of the LORD and serve him with one accord. From beyond the rivers of Cush, my worshipers, the daughter of my dispersed ones, shall bring my offering.” In the previous verse, Yahweh had commanded the believing remnant in Judah and from other lands to continue waiting on him in faith, looking through to the day of the Lord-judgment in hope. Verses 9–10 then provide one of the reasons why they must persist in their Godward trust.

On the very day of his judicial sentencing of the world (“at that time,” 3:9), Yahweh will cleanse the surviving peoples’ “speech,” which the Greek translation renders “tongue.” This speech transformation will, in turn, generate a unified profession that will result in a unified service: they will “call upon the name of the LORD and serve him with one accord” (Zeph 3:9; cf. Rev 7:9–10). The imagery of speech-purification implies the overturning of judgment (Ps 55:9) and likely alludes to a reversal of the Tower of Babel episode, where a communal pride against God resulted in his confusing “language/speech” and his “dispersing” the rebels across the globe (Gen 11:7, 9). To call on Yahweh’s name is to outwardly express worshipful dependence on him as the sovereign, savior, and satisfier (Ps 116:4, 13, 17). In Joel 2 the prophet similarly connected this phenomenon with the day of the Lord (Joel 2:28–32).

“Cush” was ancient Ethiopia, the center of black Africa, and located in modern Sudan. Its rivers were likely the White and Blue Nile (see Isa 18:1–2). As if following the rivers of life back up to the garden of Eden for fellowship with the great King (Gen 2:13; cf. Rev 22:1–2), the prophet envisions that even the most distant lands upon which the Lord has poured his wrath (Zeph 2:11–12) will have a remnant of “worshippers” whom God’s presence will compel to Jerusalem. Those gathered before God’s presence would be a worldwide, multi-ethnic community descending from the three families and seventy nations that Yahweh once “dispersed” in judgment at Babel after the flood (Gen 11:8–9). Indeed, even some from Cush, Zephaniah’s own heritage (Zeph 1:1), would gain new birth certificates declaring that they were born in Zion (Ps 87:4).

As we assess this text from the perspective of Systematic Theology, I believe it informs both our Eschatology and Ecclesiology. As for the doctrine of the last things, Zephaniah envisions that the new creation community will be born “at that time” (Zeph 3:9) when God rises as judge and executes his punishment on the world (3:8). What is significant here is that the New Testament authors view Jesus’ death to be an intrusion of the future judgment on behalf of the elect, and therefore his resurrection already inaugurates the new creation. “Since, therefore, we have now been justified by his blood, much more shall we be saved by him from the wrath of God” (Rom 5:9). “If anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come… For our sake [God] made [Christ] to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor 5:17, 21).

With respect to the doctrine of the church, Zephaniah speaks to both the disposition and international makeup of a community that God will preserve through judgment. If Jesus has already borne the day of the Lord-judgment anticipated in Zeph 3:8, it seems likely that the multi-ethnic community of worshipers he describes in 3:9–10 is indeed his church. Certainly, the depiction fulfills the hopes of the Abrahamic covenant (Gen 12:3), and it finds support in the way the New Testament sees the messianic new covenant community to be made up of Jews and Gentiles in Christ who are now one flock (John 10:16; cf. 11:51–52; 12:19–20), a single olive tree (Rom 11:17–24), and one new man (Eph 2:11–22).

In support of this view is the way Luke describes the beginnings of the church at Pentecost. The outpouring of the Spirit of Christ on the saints in Jerusalem inaugurated the change of speech and unity that Zephaniah predicted (Zeph 3:9–10). Not only does the early church speak in new “tongues” (Acts 2:4, 11; cf. 10:46; 19:6), but they also call on the name of Lord Jesus (2:21, 38) and devote themselves together “to the apostles’ teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers” (2:42). Through Christ’s atoning death, the blessing of God moves from “Jerusalem … to the end of the earth” (1:8; cf. Luke 24:47), reaching even into ancient Ethiopia/Cush, as the story of the Ethiopian eunuch testifies (Acts 8:26–40).

Now bringing together eschatology and ecclesiology, we can mark the initial fulfillment of Zephaniah’s hopes and say that already the Lord is shaping “a kingdom and priests” “from every tribe and language and people and nation” (Rev 5:9–10; cf. 7:9–10). Along with this reality, we can add that already as priests we are offering sacrifices of praise (Rom 12:1; Heb 13:15–16; 1 Pet 2:5) at “Mount Zion and … the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem” (Heb 12:22; cf. Isa 2:2–3; Zech 8:20–23). Nevertheless, we are still awaiting the day when “the holy city, new Jerusalem” will descend from heaven as the new earth (Rev 21:2). At that time, our daily journey to find rest in Christ’s supremacy and sufficiency (Matt 11:28–29; John 6:35) will be consummated in a place where the curse is no more (Rev 21:24–22:5; cf. Isa 60:3; Heb 4:1, 9–11). Thus, I believe that we can see Zephaniah’s prophetic prediction already being fulfilled today in Jesus’s church, even as we the saints await its full realization.

[1] R. Albert Mohler Jr., “Confessional Evangelicalism,” in Four Views on the Spectrum of Evangelicalism, ed. Andrew David Naselli and Collin Hansen, Counterpoints (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2011), 77–80; see also http://www.albertmohler.com/2005/07/12/a-call-for-theological-triage-and-christian-maturity/.

[2] The best book on identifying and working through these minor disagreements is Andrew David Naselli and J. D. Crowley, Conscience: What It Is, How to Train It, and Loving Those Who Differ (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2016).

This article originally appeared at FTC.co.