Text (Genre, Literary units and text hierarchy, Text-criticism)

Observation (Clause and text grammar, Argument-tracing, Word and concept studies)

Context (Historical and Literary context)

Meaning (Biblical and Systematic theology)

Application (Practical theology)

Once you have established your text, made accurate observations, and discerned your passage’s contexts, it is time to determine your text’s meaning. To do this, it is critical to understand biblical theology, the discipline that considers how the whole Bible progresses, integrates, and climaxes in Jesus. Here you ask, “How does my passage connect to the Bible’s overall storyline and point to Christ?”

Four Guiding Presuppositions

The discipline of biblical theology assumes at least four key principles about the Bible:

1. The Bible is the locus of God’s special revelation.

Every line, word, phrase, clause, and paragraph in Scripture is God’s word. No other book is like the Bible, for it alone is God’s special revelation. Therefore, biblical theology is a textual discipline, such that the author’s intent guides the connections we make both backward and forward within every text. Historical context informs and supports the study but never trumps it.

2. The Bible demands that we submit to it and engage it in constructive ways.

We must see God’s word in its final canonical form as our primary and decisive authority in all matters of faith and practice. Furthermore, our interpretation should never deconstruct the biblical text, misinterpret the text, contradict the biblical author’s intentions, or fail to evaluate fairly the claims of the text in accordance with its nature.

3. The Bible is prescriptive.

Because the Bible is God’s word, it has the authority to prescribe a certain lifestyle and worldview for its readers and to confront alternatives. God’s purpose in having us grasp his purposes in salvation history is to move us to worship and surrender to the living God through Christ.

4. The Bible expresses a coherent, unified theology.

God is the ultimate author of Scripture, and he is the ultimate unified and coherent thinker. Thus, we must push to grasp the unified theology of the whole Bible. Every passage contributes in some way to the whole.

Definition and Nature of Biblical Theology

The whole Bible progresses, integrates, and climaxes in Christ, and every passage contributes in some way to Scripture’s message that God reigns, saves, and satisfies through covenant for his glory in Jesus. Central to determining a passage’s meaning is not only considering what it proclaims but how this message relates to and informs the greater message of Scripture culminating in Christ.

Biblical theology is a way of analyzing and synthesizing what the Bible reveals about God and his relations with the world that makes organic salvation-historical and literary-canonical connections with the whole of Scripture on its own terms, especially with respect to how the Old and New Testaments progress, integrate, and climax in Christ. Let me unpack this extended definition under six headings.

- The Task, Part 1: Biblical theology analyzes and synthesizes what the Old and New Testaments reveal about God and his relations with the world.

Biblical theology seeks to interpret the final form of the Christian Bible––to analyze and synthesize God’s special revelation embodied in the Old and New Testaments. That God’s special revelation comes through Old and New Testaments highlights both Scripture’s unity and diversity. The one Bible has two necessary parts, each of which we must read in view of the other. The Old Testament provides foundation for what Jesus fulfills in the New Testament.

- The Task, Part 2: Biblical theology makes organic connections with the whole of Scripture on its own terms.

Biblical theology is about making natural, unforced connections within Scripture. In the process, it recognizes growth or progress in a thought or concept and lets the Bible speak in accordance with its own contours, structures, language, and flow.

- Salvation-Historical Connections: Biblical theology makes salvation-historical connections with the whole of Scripture on its own terms.

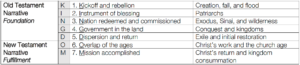

Salvation history is the progressive narrative unfolding of God’s kingdom plan through the various covenants, events, people, and institutions, all climaxing in the person and work of Jesus. Redemptive history moves from creation to the fall to redemption to consummation. It’s the true story of God’s purposes climaxing in Christ that frames all of Scripture from Genesis to Revelation. One way to summarize his-story is through the acronym KINGDOM, as represented in the following chart:

Scripture declares the story of God’s glory in Christ. Within this framework, we can make salvation-historical connections in at least five different ways:

- Thematic developments: We can trace a theme through the story of salvation, noting how it culminates in Christ. Some of the main themes are kingdom, law, temple, people of God, exile and exodus, atonement, holiness, and missions.

- Covenantal continuity and discontinuity: We should consider how the progress of the biblical covenants maintains, transforms, alters, or escalates various elements in God’s relations with his people and the world.

- Type and anti-type: Both Old and New Testament authors regularly identify predictive thematic anticipations or types rooted in the progressive development of Scripture’s historical record (e.g., Rom. 5:14; 1 Cor. 10:6, 11; Col. 2:16–17). By God’s design, specific persons (e.g., Adam, Moses), events (e.g., creation, exodus), and institutions (e.g., temple, sacrifice) establish patterns that culminate in the life and work of Christ Jesus. These types are prophetic and prospective from their inception, even when interpreters only discover them retrospectively.

- Promise and fulfillment: We must track specific promises and then identify their partial, progressive, and/or ultimate fulfillment at various stages in salvation history, ever remembering Paul’s declaration that “all the promises of God find their Yes in [Christ]” (2 Cor. 1:20). An example here would be how Micah 5:2 declares that the royal deliver would rise out of Bethlehem, and Matthew declares this fulfilled (Matt. 2:5–6).

- Use of the Old Testament in the Old and New Testaments: Here, we assess how later biblical writers interpret and/or apply earlier canonical revelation, especially with a view to understanding Christ Jesus.

- Literary-Canonical Connections: Biblical theology makes organize literary-canonical connections with the whole of Scripture on its own terms.

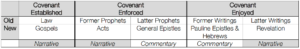

Biblical theology arises out of the narrative framework of salvation history, but we cannot restrict the discipline to redemptive historical connections because the Bible includes more than the story of God’s glory in Christ. As seen below, Scripture includes groupings of narrative books that frame commentary books. We must consider every passage in light of its placement and role within the canon as a whole, which contains two Testaments, each with corresponding narrative and commentary sections and each with a potentially-corresponding three-part structure. The chart arranges the Old Testament in alignment with the order in Jesus’s Bible (see Luke 24:44) and the New Testament in accordance with the earliest canonical evidence.

Along with final-form composition and structure, literary-canonical connections include the historical details that tie the canon together. Here I refer to information regarding authorship, date, or provenance of a given passage. Where God reveals such information, it is fair and appropriate to use it to consider how books or passages that are united historically address various themes or contribute to our knowledge of a given topic. Because Moses was the substantial author of both Exodus and Leviticus, we can use each book as an interpretive lens for the other. Because Samuel–Kings and Chronicles address similar time-periods from different perspectives, we can compare the two to help clarify the distinctive theology of each corpus.

Finally, literary-canonical connections also include accounting for our passage’s biblical corpus or genre. Studying the teaching in Ecclesiastes should naturally be related to that of Proverbs not only because Solomon is likely the same author but also because both are wisdom books. Similarly, one should interpret Zephaniah in view of its placement in and contribution to both the Book of the Twelve and the Latter Prophets as a whole.

- Relationship of the Testaments: Biblical theology wrestles with how the Old and New Testaments progress and integrate.

The relationship of the Testaments is perhaps the biggest question faced in biblical theology. Scripture was not shaped in a day. God produced it over time, progressively disclosing his kingdom purposes climaxing in Christ and pointing ultimately to the consummation. Biblical theology gives significant effort to tracking this progression and to considering how the various covenants and Testaments integrate in God’s overarching kingdom plan.

- The Centrality of Christ: Biblical theology wrestles with how the Old and New Testaments climax in Christ.

The ultimate end of biblical theology is Jesus. The salvation history that frames Scripture all points and progresses to Christ, and all fulfillment flows from and through him. All laws, history, laws, prophecy, and promises find their end-times realization in Jesus (Matt 5:17–18; Mark 1:15; Acts 3:18; 2 Cor. 1:20). Therefore, we can rightly assert that the Old Testament is a messianic document written to instill messianic hope (see Rom. 1:1–3; 3:21; 10:4). Indeed, the apostles recognized that Yahweh foretold by the mouth of all the prophets from Moses forward the tribulation and triumph of the Christ and the subsequent glories (Acts 3:18, 24; 10:43; 1 Peter 1:10–11), and God revealed to those prophets that “they were serving not themselves but you” when they wrote their words (1 Peter 1:12). If we fail to appreciate that the Old Testament is Christian Scripture, we do not approach it like Jesus and his apostles, and we have no basis to call our interpretation “Christian.”

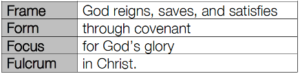

The Bible’s Frame, Form, Focus, and Fulcrum

Thus far, we have learned something about what the Bible is about, how it is transmitted, why it was given, and around whom it is centered. That is, the Bible has a frame, a form, a focus, and a fulcrum.

- The Frame = The Content: What?

The Bible is the revelation of God, who reigns over all and who saves and satisfies all who look to him. In short, Scripture is about his kingdom and how he builds it through covenant for his glory in Christ. We could say that Scripture’s content relates to God’s reign over God’s people in God’s land for God’s glory (Luke 4:43; Acts 1:3; 20:25; 28:23, 31).

- The Form = The Means: How?

Throughout salvation history, God has maintained his relationship with the world through a series of covenants. The most dominant of these are the Mosaic (old) covenant and the new covenant in Christ. The old covenant bore a ministry of condemnation and brought forth an age of death; the new covenant bore a ministry of righteousness and brought with it life (2 Cor. 3:9). Moses recognized Israel’s stubbornness and predicted the old covenant’s failure (Deut. 9:6–7; 31:16–18, 27–29). But he also envisioned that God would mercifully overcome the curse with restoration blessing (4:30–31) in what we now know as the new covenant (Jer. 31:31). A prophetic, new covenant mediator would facilitate this era of blessing (Deut. 18:15), which would include God’s transforming the hearts of covenant members in a way that would generate love and obedience (30:6, 8–14). God would curse all his enemies (30:7) and broaden the makeup of his people to include some from the nations (32:21, 43; cf. Gen. 17:4–5). Christ is the mediator of the new covenant (Gen. 22:17–18; 1 Tim. 2:5; Heb. 9:15; 12:24), which has superseded the old (Gal. 3:24–25; Rom. 10:4), made every promise “Yes” (2 Cor. 1:20), and secured for us every spiritual blessing (Eph. 1:3) and “an inheritance that is imperishable, undefiled, and unfading” (1 Peter 1:4).

- The Focus = The Purpose: Why?

The chief goal of all God’s actions is the preservation and display of his glory, and it is to this end that all Scripture points. Because all things are from him, through him, and to him, God’s glory is exalted over all things (Rom. 11:36) and should be the goal of our lives (1 Cor. 10:31).

- The Fulcrum = Sphere: Whom?

Jesus Christ is the one to whom all salvation history points, and the one who fulfills all the Old Testament anticipates. The entire Bible centers on this promised messianic Deliverer who secures reconciliation with God for all who believe in him as the divine, crucified, resurrected Messiah. His ministry produces a universal call to repentance and whole-life surrender to him as King.

We can synthesis Scripture’s as God reigns, saves, and satisfies through covenant for his glory in Christ. Put another way, the Bible calls Jews and Gentiles alike to magnify God as the supreme Sovereign, Savior, and Satisfier of the world through Messiah Jesus. The Old Testament provides the foundation for this message; the New Testament fulfills all Old Testament hopes.[1]

Conclusion

Scripture is self-interpreting, for the God who never changes is the author of it all. To determine the full meaning of a passage, we must always ponder how your passage contributes and relates to the rest of Scripture culminating in Christ. The whole Bible progresses, integrates, and climaxes in Jesus, so we must consider how every passage in the Old Testament relates to this overarching flow and message.

[1] For two examples of biblical theology at work, see Jason S. DeRouchie, “Why the Third Day?: The Promise of Resurrection in All of Scripture,” Desiring God, 11 June 2019, https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/why-the-third-day; Jason S. DeRouchie, “God Always Wanted the Whole World: Global Mission from Genesis to Revelation,” Desiring God, 5 December 2019, https://www.desiringgod.org/articles/god-always-wanted-the-whole-world.

This article originally appeared at FTC.co.