Step #1: Genre

When my oldest daughter was younger, she was a master of “genre” analysis. I saw it most clearly after her daily trip to the mailbox, when she would push aside the bills and advertisements to select the letters from friends or family. With every new piece of literary composition, we almost always identify its genre. We decide (consciously or unconsciously) whether a text is a research paper or poem, a factual history or a fairy tale. We look for clues in format, presentation, introductory or closing statements, and content. We seek the author’s signals as to whether something is satire, fiction, or non-fiction. These markers point to a document’s genre.

Genre: Goal, Definition, and Purpose

The first step of exegesis is to understand genre, which is also the initial step in determining the text’s makeup (i.e., establishing the Text). When assessing genre, the goal is to determine the literary form, subject matter, and function of your focus passage, to compare it to similar genres, and to consider the implications for interpretation. Genre refers to an identifiable category of literary composition that usually demands its own exegetical rules. In addition, different genres have different functions, with some existing to convey information or stir thoughts (e.g., laws and historical narratives) and others affecting and effecting certain behaviors, beliefs, and feelings (e.g., psalms and love songs). Accordingly, a misunderstanding of a work’s genre can lead to skewed interpretation. Our decisions at this point will color the rest of the interpretive process.

For king David, the prophet Nathan’s words about the robbed lamb switched from an historical narrative about someone else’s injustice to a narrative parable about his own injustice through the single statement, “You are the man!” (2 Sam 12:1–7). The context guided his genre analysis, and the result was the recognition of his horrific sin.

A Sampling of Old Testament Genres

The Bible contains many genres, the most frequent of which are historical narratives, covenant stipulations (i.e., laws), prophecies, psalms, and proverbs. All of these primary genres contain multiple sub-genres. Historical narratives, for example, can include biographies (Gen 38), songs (Exod 15:1–18), riddles (Judg 14:14), genealogies (Ruth 4:18–22), birth and death accounts (1 Sam 1, 31), and the like. Most of the covenant stipulations themselves are built within historical narrative accounts and come in two forms––base principles (apodictic law, Exod 20:3) and situational guidelines (case law, Exod 21:28). The stipulations themselves address all spheres of life including criminal offenses (Deut 24:7), civil disputes (Exod 22:2–3), family laws (Deut 25:5–6), cultic or ceremonial legislation (Exod 20:24–26), and guidelines for compassion (Deut 14:28–29). Prophecies appear as indictments (Mic 3:8), instructions (Zeph 2:3), warnings or predictions of punishment (Amos 4:1–3), and hopeful promises of salvation (Zech 8:7–8). According to 1 Chronicles 16:5, the most basic sub-genres of psalms are invocation or lament (Ps 3), thanksgiving (Ps 30), and praise (Ps 117), though scholars often delimit more categories. While the Book of Proverbs includes both general instruction and predictions, the most dominant genre is the proverb, which is a succinct, memorable saying in common use that states a general truth or piece of advice. Many proverbs are for specific occasions and address ultimate truths about the future and not immediate truths for the present age (cf. Prov 10:27; 11:20; 13:21).

Putting Genre within Its Biblical Context

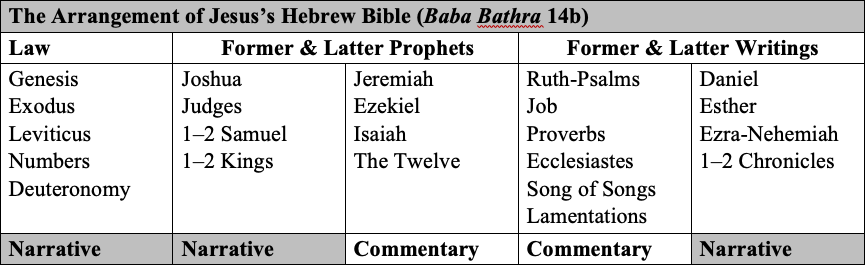

The Jewish Bible that Jesus and the apostles had included the same books as our English Old Testament (OT) but arranged some elements differently. Not only did it pair some books into single volumes that our English Bible’s separate (Samuel, Kings, the Twelve [minor prophets], Ezra-Nehemiah, Chronicles),[1] it also arranged the whole in a different order and in three main divisions: the Law (tôrâ), the Prophets (něbîʾîm), and the Writings (or “the other Scriptures,” kětûbîm).[2] The biblical evidence also suggests that Jesus’ Bible began with Genesis and ended with Chronicles.[3]

The canonical arrangement I am following here is not that of the standard critical edition of the Hebrew Bible but is found in the most ancient listing of the Jewish canonical books dated to around the days of Christ and located in Baba Bathra 14b. As is evident in the figure below, the biblical historical narrative runs chronologically from Genesis to Kings, pauses from Jeremiah to Lamentations, and then resumes from Daniel to Ezra-Nehemiah. Chronicles then recalls the story from Adam to Cyrus’s decree that Israel can return. As for the commentary, the Latter Prophets structure the four books largest to smallest, and the Former Writings follow the same pattern, except that Ruth prefaces the Psalter and the longer Lamentations follows Song of Songs. I could say much more about the ordering of Jesus’ Bible,[4] but two things are important to recognize here: (1) Historical narrative frames the entire OT, which means that the (true) story of God’s work to bring about the Messiah to save the world provides the lens for understanding everything else. (2) The OT also includes non-narrative prophetic and poetic commentary books that color, clarify, and control our reading of the narrative itself.

An Exercise in Genre Analysis: Historical Narrative

For our exercise in genre analysis, we will consider the historical narrative of Jonah. We are analyzing historical narrative since it constitutes 65% of the OT. To rightly interpret historical narrative, the interpreter must follow five guidelines.

1. Distinguish the episode and its scenes.

The term “episode” in OT exegesis is related to its use in a TV series like 24. In 24, each season consists of twenty-four one-hour long episodes that build upon each other and carry the storyline forward. Within each episode, there might be six-twelve individual scenes that take us through the equivalent of 60 minutes in the lives of the characters. To understand 24 and shows like it, one must be able to grasp how each scene contributes to the message of each episode, and how each episode contributes to the overall storyline of the season. Likewise, we should break each biblical book of historical narrative into its episodes and then identify how the scenes of that episode work together to communicate the main point of the episode.

Within the book of Jonah, 1:1–2:10 is the first “episode” and 3:1–4:11 is the second “episode.” We can identify these portions of Scripture as episodes because they both begin with, “Now the word of the LORD came to Jonah” (Jon 1:1; 3:1). Noting shifts in participant, context, and grammar, the first episode appears to consist of four “scenes.” These scenes are (1) Yahweh’s call to go on mission (1:1–2), (2) Jonah’s rebellion (1:3–16), (3) Yahweh’s response to Jonah’s rebellion (1:17), and (4) Jonah’s response to Yahweh’s mercy (2:1–10). Where does the text suggest the scene-breaks are in episode 2 (3:1–4:11)?

2. Consider literary features.

Having identified the scenes from the episodes, we now consider literary features. This involves examining the literary context, plot development and characterization, and editorial comments. To understand the literary context, examine what comes before and after your passage, seeking to grasp how your episode’s literary placement fits within the narrative’s flow. Track the plot development and characterization of a historical narrative by discerning the nature of the conflict and its resolution, God’s role in the narrative, and how humans’ words and deeds relate to their covenant with God.

The book of Jonah lacks any significant editorial comments, but there are a number of other literary features that are significant. With respect to literary context, the first episode ends with Jonah celebrating his own experience of God’s steadfast love (2:8–9), but the second episode shows Jonah detesting that his enemies experience God’s steadfast love (3:9–4:2). As for plot development and characterization, in episode one, Yahweh is clearly the main character, with Jonah appearing only as a foil to exalt God’s sovereignty and steadfast love. Yahweh calls Jonah to Nineveh; Yahweh sends the storm, and Yahweh intensifies it to keep the sailors from rescuing the prophet; Yahweh provides the fish to rescue Jonah; and Yahweh is the object of Jonah’s praise from the fish’s belly. Jonah is grateful that Yahweh saves him from the fish, but in episode two he will be angry that Yahweh saves Nineveh from punishment. The prophet of Yahweh does not like Yahweh’s character, and this is real irony. What literary features can you identify in episode 2?

3. State in a single sentence the narrative episode’s main idea.

The main idea of a historical narrative episode is usually found within a speech and almost always tells us something about God or how we relate to him. In Jonah’s prayer at the end of episode one, he links Yahweh’s saving acts with people’s hope in his steadfast love: “Those who pay regard to vain idols forsake their hope of steadfast love…. Salvation belongs to the LORD!” (2:8–9). Then, toward the end of episode two, the prophet prays again, highlighting why he never wanted to go to Nineveh in the first place: “I knew that you are a gracious God and merciful, slow to anger and abounding in steadfast love, and relenting from disaster” (4:2; cf. Exod 34:6). The book seems to be highlighting the Lord’s loving character and saving action, and we must interpret the scenes and episodes in light of it. Doing this yields the following single sentence main idea for Jonah’s first episode (Jon 1:1–2:10): God desires that people personally hope in and experience his saving, steadfast love! How would you craft the main idea of episode two?

4. Draft an exegetical outline of the narrative episode that aligns with the passage’s purpose.

Having paid close attention to the preceding three historical narrative guidelines, we are now able to draft a message-driven outline that demonstrates how the various scenes work together to create a unified episode. This outline could in turn serve as the very structure for a sermon or lesson. Keeping in mind episode one’s scene divisions and main idea, I propose the following outline, which attempts to show how the idea of steadfast love holds the whole message together:

- Jonah’s first experience of Yahweh’s steadfast love (1:1–2:10)

- Yahweh’s initial call to a mission of steadfast love (1:1–2)

- Jonah’s personal need for steadfast love (1:3–16)

- Yahweh’s demonstration of steadfast love (1:17)

- Jonah’s positive response to Yahweh’s steadfast love (2:1–10)

- Jonah’s second experience of Yahweh’s steadfast love (3:1–4:11)

How would you complete the outline for episode two?

5. Evaluate the passage’s theological trajectories.

Here we ask questions like, Is the passage more about believing or doing? What does it tell us about the unchanging, triune God’s character or actions? And how does it anticipate the person and work of Christ? It is in this step that we will most grasp the passage’s lasting value for Christians today.

Jonah exalts Yahweh as a God whose steadfast love moves him to save all who look to him. The book encourages people to personally hope in his steadfast love by turning from idols, but it also challenges people to guard their hearts from withholding such saving, steadfast love from others. One of the ways the book anticipates Christ is that it reveals God’s deep desire to be gracious and compassionate to sinful humanity, and this desire is most ultimately manifest in the glorious grace (steadfast love) and truth (faithfulness) that come through Jesus (John 1:14, 17; cf. Exod 34:6; Jon 4:2).

*Material adapted from “Chapter 1: Genre” in DeRouchie’s How to Understand and Apply the Old Testament, 21–97.

Editor’s Note: This is Part 2 of a 12-part series from Dr. Jason DeRouchie. View the previous posts in the series here.

[1] Note, for example, how Acts 7:42–43 speaks of a single “book of the prophets” and then cites Amos 5:25–27.

[2] Besides evidence from outside the Bible, we see evidence of this three-part structure when Jesus declared after his resurrection, “These are my words that I spoke to you while I was still with you, that everything written about me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled” (Luke 24:44).

[3] We see this in one of Jesus’s confrontations with the Pharisees, in which he spoke of the martyrdom of the OT prophets “from the blood of Abel to the blood of Zechariah” (Luke 11:51; cf. Matt 23:35). Jesus appears to have been speaking canonically, mentioning the first and last martyr in his Bible’s literary structure. Specifically, just as Genesis records Abel’s murder, the end of Chronicles highlights a certain Zechariah who was killed in the temple court during the reign of Joash (835–796 BC; see 2 Chr 24:20–21).

[4] See Jason S. DeRouchie, “Is the Order of the Canon Significant for Doing Biblical Theology?,” in 40 Questions about Biblical Theology, by Jason S. DeRouchie, Oren R. Martin, and Andrew David Naselli, 40 Questions (Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2020), 157–70.

****

This article originally appeared at FTC.co.